How Does Climate Change Affect The Economy

Introduction: Scientific Groundwork

Substantial Biophysical Damages Will Occur in the Absence of Strong Climate Policy Activeness

The earth'south climate has already changed measurably in response to accumulating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These changes besides every bit projected future disruptions have prompted intense research into the nature of the problem and potential policy solutions. This certificate aims to summarize much of what is known almost both, adopting an economic lens focused on how aggressive climate objectives tin exist achieved at the lowest possible cost.

Considerable uncertainties surround both the extent of hereafter climatic change and the extent of the biophysical impacts of such change. Yet the uncertainties, climate scientists accept reached a strong consensus that in the absence of measures to reduce GHG emissions significantly, the changes in climate will exist substantial, with long-lasting effects on many of Earth'southward physical and biological systems. The central or median estimates of these impacts are significant. Moreover, in that location are significant risks associated with low probability but potentially catastrophic outcomes. Although a focus on median outcomes lonely warrants efforts to reduce emissions of GHGs, economists argue that the uncertainties and associated risks justify more ambitious policy action than otherwise would be warranted (Weitzman 2009; 2012).

The scientific consensus is expressed through summary documents offered every several years by the Un–sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change (IPCC). These documents betoken the projected outcomes under culling representative concentration pathways (RCPs) for GHGs (IPCC 2014). Each of these RCPs represents unlike GHG trajectories over the side by side century, with college numbers corresponding to more emissions (see box 1 for more on RCPs).

Box 1. Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs)

The expected path of GHG emissions is crucial to accurately forecasting the physical, biological, economic, and social furnishings of climate change. RCPs are scenarios, chosen by the IPCC, that represent scientific consensus on potential pathways for GHG emissions and concentrations, emissions of air pollutants, and country employ through 2100. In their most-contempo assessment, the IPCC selected four RCPs as the basis for its projections and analysis. Nosotros describe the RCPs and some of their assumptions below:

- RCP two.half-dozen: emissions peak in 2020 and then decline through 2100.

- RCP 4.five: emissions summit between 2040 and 2050 and then decline through 2100.

- RCP half-dozen.0: emissions keep to rise until 2080 and and so turn down through 2100.

- RCP viii.5: emissions rising continually through 2100.

The IPCC does not assign probabilities to these different emissions pathways. What is clear is that the pathways would require different changes in engineering science and policy. RCPs 2.6 and 4.5 would very likely require pregnant advances in technology and changes in policy in social club to be realized. Information technology seems highly unlikely that global emissions will follow the pathway outlined in RCP two.half dozen in particular; annual emissions would have to start declining in 2020. By contrast, RCPs half-dozen.0 and viii.5 represent scenarios in which future emissions follow past trends with minimal to no change in policy and/or engineering science.

The 4 RCPs imply different effects on global temperatures. Figure A indicates the projected increases in temperature associated with each RCP scenario (relative to preindustrial levels).one The figure suggests that simply the meaning reductions in emissions underlying RCPs 2.6 and 4.five can stabilize average global temperature increases at or around 2°C. Many scientists have suggested that it is critical to avoid increases in temperature beyond 2°C or fifty-fifty 1.5°C—larger temperature increases would produce extreme biophysical impacts and associated man welfare costs. It is worth noting that economic assessments of the costs and benefits from policies to reduce COii emissions do not necessarily recommend policies that would constrain temperature increases to i.5°C or ii°C. Some economic analyses suggest that these temperature targets would exist as well stringent in the sense that they would involve economic sacrifices in backlog of the value of the climate-related benefits (Nordhaus 2007, 2017). Other analyses tend to support these targets (Stern 2006). In scenarios with little or no policy action (RCPs 6.0 and 8.5), boilerplate global surface temperature could rising 2.9 to 4.3°C above preindustrial levels past the terminate of this century. One consequence of the temperature increase in these scenarios is that ocean level would ascent by between 0.5 and 0.8 meters (effigy B).

Countries' Relative Contributions to COii Emissions Are Changing

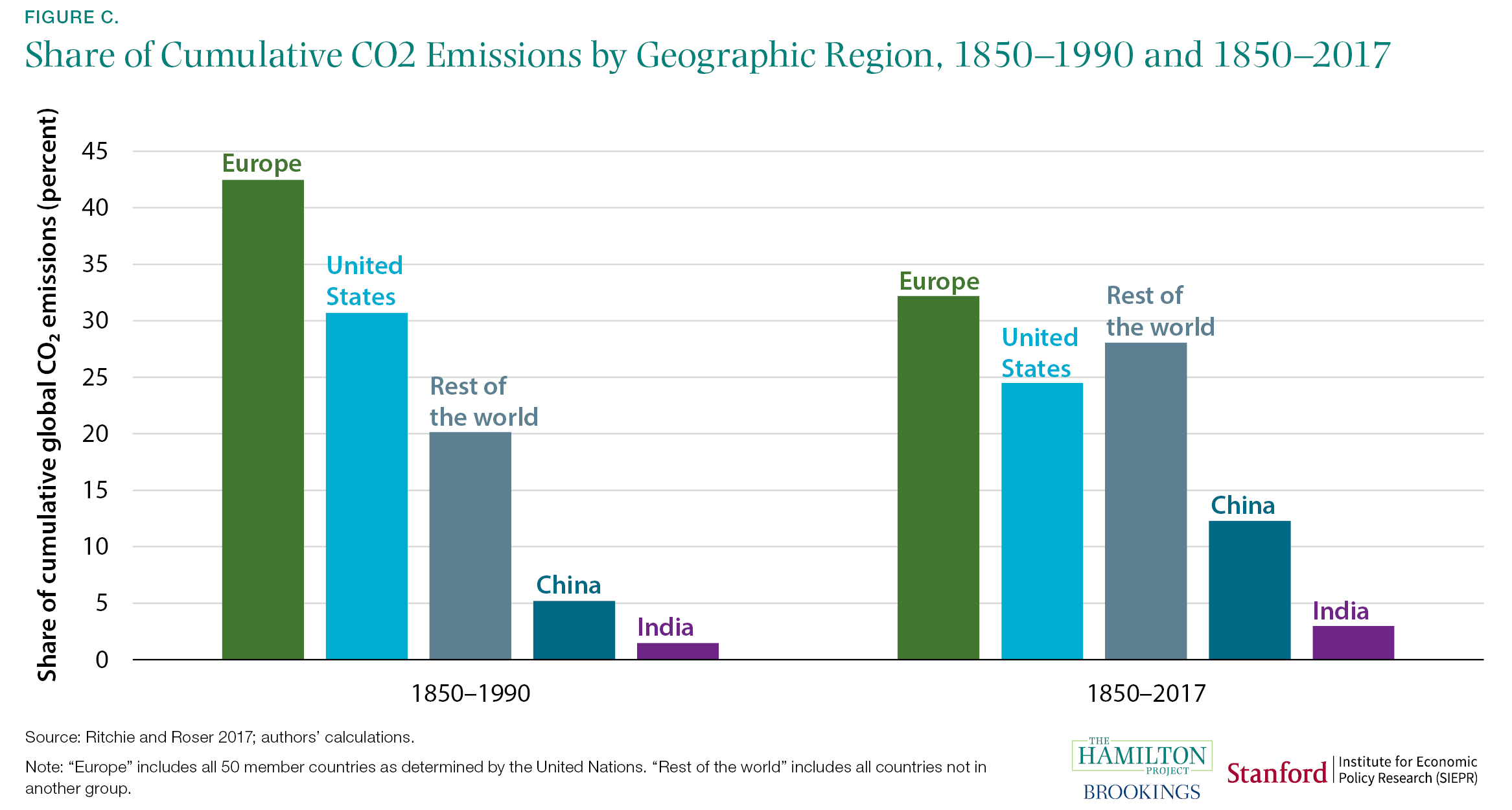

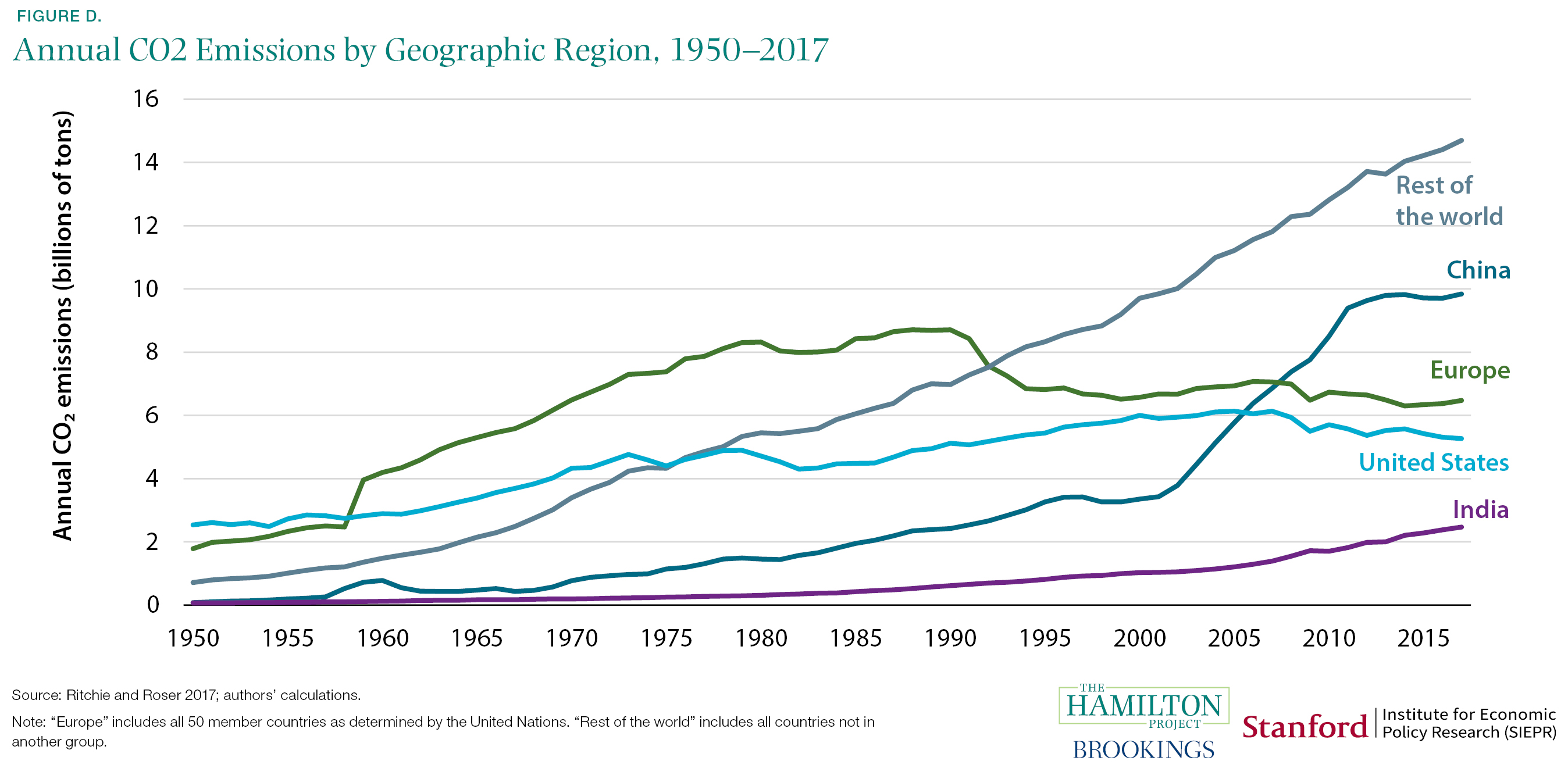

The extent of climatic change is a role of the atmospheric stock of COtwo and other greenhouse gases, and the stock at any given betoken in time reflects cumulative emissions upwardly to that point. Thus, the contribution a given country or region makes to global climate modify can be measured in terms of its cumulative emissions.

Upwardly to 1990, the historical responsibleness for climatic change was primarily owing to the more-industrialized countries. Between 1850 and 1990, the U.s.a. and Europe alone produced nearly 75 percent of cumulative CO2 emissions (encounter figure C). Such historic responsibleness has been a chief issue in debates nearly how much of the brunt of reducing current and future emissions should fall on the shoulders of developed versus developing countries.

Although the United states and other adult nations continue to be responsible for a large share of the current backlog concentration of COtwo, relative contributions and responsibilities are changing. Every bit of 2017, the United States and Europe deemed for but over 50 percent of cumulative COtwo emitted into the temper since 1850. A reason for this sharp decline (as indicated in figures C and D) is that COii emissions from China, India, and other developing countries have grown faster than emissions from the developed countries (though amongst major economies, the The states has i of the highest rates of per capita emissions in the world and is far alee of China and Republic of india [Joint Inquiry Centre 2018]). Therefore, it seems probable that in order to avert the worst effects of climate change, emissions reduction efforts volition be required by both historic contributors—the United States and Europe—as well as more recently developing countries such as China and Bharat.

Nations' Pledges under the Paris Agreement Imply Significant Reductions in Emissions, only Not Enough to Avoid a 2°C Warming

The future of climate change might seem dismal in light of the recent increase in global emissions as well as the potential future growth in emissions, temperatures, and ocean levels under RCPs six.0 and 8.5. Failure to take any climate policy action would lead to almanac emissions growth rates far above those that would foreclose temperature increases beyond the focal points of ane.five°C and 2°C (figure E). As indicated earlier, toll-benefit analyses in various economic models lead to differing conclusions every bit to whether it is optimal to constrain temperature increases to 1.v°C or 2°C (Nordhaus 2007, 2016; Stern 2006).two Fortunately, countries have been taking steps to combat climate modify, referred to in figure E equally "Electric current policy" (which includes policy commitments made prior to the 2015 Paris Agreement). Comparing "No climate policies" and "Current policy" shows that the emissions reduction implied by current policies will pb to roughly 1°C lower global temperature by the end of the century. A big share of this lowered emission path is owing to actions by states, provinces, and municipalities throughout the globe.

Farther reductions are implied by the 2015 Paris Agreement, nether which 195 countries pledged to have boosted steps. The Paris Agreement's pledges, if met, would continue global temperatures 0.5°C lower than "Electric current policy" and almost 1.5°C lower than "No climate policy" in 2100 (meet figure E). Although this can be viewed as a positive result, a morenegative perspective is that these policies would still allow temperatures in 2100 to be 2.6 to 3.2°C above preindustrial levels—significantly to a higher place the 1.5 or 2.0°C targets that have go focal points in policy discussions.

In the post-obit set of facts, we describe the costs of climatic change to the United States and to the world every bit well as potential policy solutions and their corresponding costs.

Fact 1: Damages to the U.Southward. economy grow with temperature modify at an increasing rate.

The concrete changes described in the introduction will have substantial furnishings on the U.S. economy. Climatic change will touch agricultural productivity, mortality, crime, energy use, storm activity, and littoral overflowing (Hsiang et al. 2017).

In figure 1 nosotros focus on the economic costs imposed by climatic change in the Us for different cumulative increases in temperature. Information technology is immediately apparent that economic costs will vary greatly depending on the extent to which global temperature increment (in a higher place preindustrial levels) is limited by technological and policy changes. At 2°C of warming by 2080–99, Hsiang et al. (2017) project that the United States would suffer almanac losses equivalent to most 0.5 percent of Gdp in the years 2080–99 (the solid line in figure 1). By contrast, if the global temperature increment were every bit large as 4°C, annual losses would be effectually two.0 percent of GDP. Importantly, these effects become disproportionately larger as temperature rise increases: For the Usa, ascent mortality every bit well equally changes in labor supply, energy need, and farm production are all especially important factors in driving this nonlinearity.

Looking instead at per capita GDP impacts, Kahn et al. (2019) find that annual GDP per capita reductions (as opposed to economic costs more broadly) could be between 1.0 and 2.8 percent under IPCC's RCP 2.6, and under RCP 8.five the range of losses could be between half dozen.seven and fourteen.3 percent. For context, in 2019 a 5 pct U.South. GDP loss would be roughly $one trillion.

There is, of course, substantial incertitude in these calculations. A major source of uncertainty is the extent of climatic change over the next several decades, which depends largely on future policy choices and economic developments—both of which affect the level of total carbon emissions. As noted earlier, this uncertainty justifies more ambitious action to limit emissions and thereby help insure against the worst potential outcomes.

Information technology is also important to highlight what figure 1 leaves out. Economic furnishings that are not readily measurable are excluded, as are costs incurred past countries other than the United States. In addition, if climate change has an impact on the growth rate (as opposed to the level) of output in each year, then the impacts could chemical compound to exist much larger in the future (Dell, Jones, and Olken 2012).3

Fact two: Struggling U.S. counties will be hit hardest by climate change.

The effects of climate change volition non exist shared evenly beyond the United States; places that are already struggling volition tend to exist hit the hardest. To explore the local impacts of climate change, we utilise a summary measure of county economic vitality that incorporates labor market, income, and other data (Nunn, Parsons, and Shambaugh 2018), paired with county level costs equally a share of Gross domestic product projected by Hsiang et al. (2017).4

Effigy 2 shows that the bottom fifth of counties ranked past economic vitality volition experience the largest damages, with the bottom quintile of counties facing losses equal in value to nearly vii percent of Gross domestic product in 2080–99 nether the RCP 8.5 scenario (a projection that assumes little to no additional climate policy action and warming of roughly four.3°C to a higher place preindustrial levels).5 Counties that will be hitting hardest by climate change tend to be located in the Due south and Southwest regions of the United States (Muro, Victor, and Whiton 2019). Rao (2017) finds that nearly two million homes are at risk of being underwater by 2100, with over half of those being located in Florida, Louisiana, Northward Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas. More-prosperous counties in the U.s.a. are oft in the Northeast, upper Midwest, and Pacific regions, where temperatures are lower and communities are less exposed to climate impairment.

An important limitation of these estimates is that they assume that population in each county remains constant over time (Hsiang et al. 2017).6 To the extent that people will suit to climate change by moving to less-vulnerable areas, this adjustment could assist to diminish aggregate national damages but may exacerbate losses in places where employment falls. Moreover, the limited ability of low-income Americans to migrate in response to climatic change exposes them to particular hardship (Kahn 2017).

The concentration of climate damages in the South and amid low-income Americans implies a disproportionate impact on minority communities. Geographic disadvantage is overlaid with racial disadvantage (Hardy, Logan, and Parman 2018), and Black, Latino, and indigenous communities are probable to comport a asymmetric share of climatic change burden (Adventure and Balbus 2016).

Fact 3: Globally, low-income countries will lose larger shares of their economic output.

Different other pollutants that have localized or regional furnishings, GHGs produce global effects. These emissions found a negative spillover at the widest scale possible: For case, emissions from the U.s.a. contribute to warming in China, and vice versa. Moreover, some places are much more exposed to economical damages from climate change than are other places; the same increase in atmospheric carbon concentration will crusade larger per capita damages in India than in Iceland.

This means that carbon emissions and the amercement from those emissions can be (and, in fact, are) distributed in very different means. Figure 3 shows impacts on per capita GDP based on a study of the Gdp growth effects of warming, highlighting the relatively high per capita income reductions in Latin America, Africa, and Due south Asia (though higher-income countries would lose more absolute aggregate wealth and output considering of their higher levels of economic activeness). The figure besides uses a higher approximate of potential economical amercement that takes into account impacts on productivity and growth that accumulate over fourth dimension as opposed to looking at snapshots of lost activity in a given year. Thus, the estimates are college than those presented in facts 1 and 2, highlighting both the doubtfulness and the potentially disastrous outcomes that are possible.

Beyond showing the potentially destructive scale, this map suggests global inequity: Several of the regions that contribute relatively footling to the climate modify problem—regions with relatively low per capita emissions—still endure relatively high climate amercement per capita.

Fact iv: Increased bloodshed from climate change will exist highest in Africa and the Middle E.

The reductions in economic output highlighted in fact 3 are not the only damages expected from climatic change. One of import case is the result of climate change on mortality. In places that already experience high temperatures, climate change will exacerbate heat-related health issues and cause mortality rates to ascension.

Figure 4 relies on estimates from Carleton et al. (2018) to show climatic change's expected effects on mortality in 2100. The geographical distribution of the bear upon on mortality is very uneven. Some of the almost-significant impacts are in the equatorial zone because these locations are already very hot, and loftier temperatures become increasingly dangerous as temperatures ascent farther. For example, Accra, Ghana is projected to experience 160 boosted deaths per 100,000 residents. In colder regions, mortality rates are sometimes predicted to autumn, reflecting decreases in the number of dangerously cold days: Oslo, Kingdom of norway is projected to feel 230 fewer deaths per 100,000. But for the globe equally a whole, negative effects are predominant, and on boilerplate 85 additional deaths per 100,000 volition occur (Carleton et al. 2018).

Also axiomatic in figure 4 is the role of income. Wealthier places are better able to protect themselves from the adverse consequences of climate change. This is a cistron in projections of bloodshed risk from climate change: the bottom third of countries by income will experience almost all of the total increment in mortality rates (Carleton et al. 2018).

Mortality effects are disproportionately concentrated amid the elderly population. This is true whether the effects are positive (when dangerously cold days are reduced) or negative (when dangerously hot days are increased) (Carleton et al. 2018; Deschenes and Moretti 2009).

Fact 5: Energy intensity and carbon intensity have been falling in the U.S. economy.

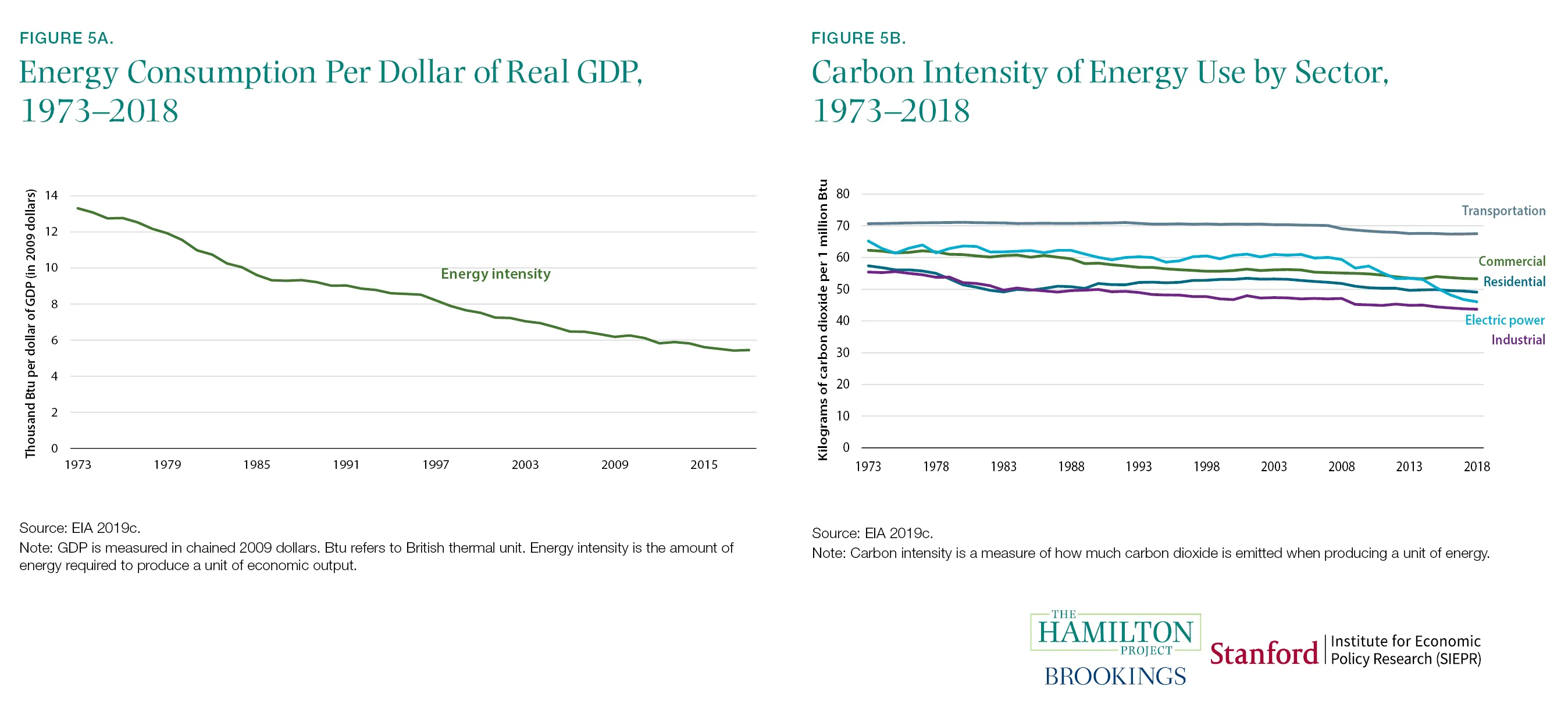

The high-damage climate outcomes described in previous facts are not inevitable: There are good reasons to believe that substantial emissions reductions are attainable. For example, non merely has the emissions-to-GDP ratio of the U.Due south. economic system declined over the by two decades, just during the concluding decade the accented level of emissions has declined too, despite the growth of the economy. From a superlative in 2007 through 2017, U.S. carbon emissions accept fallen fourteen percent while output grew 16 per centum (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2007–17; U.Southward. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] 2007–17; authors' calculations). This reversal was produced by a combination of declining energy intensity of the U.S. economy (figure 5a) and declining carbon intensity of U.S. energy apply (figure 5b). Yet, emissions increased in 2018, which suggests that sound policy will be needed to continue making progress (Rhodium Group 2019).

U.S. energy intensity (defined as energy consumed per dollar of Gdp) has been falling both in times of economic expansion and wrinkle, allowing the economy to grow even as free energy utilize falls. This has been crucial for mitigating climate change damages (CEA 2017; Obama 2017). Some estimates suggest that declining energy intensity has been the biggest contributor to U.S. reductions in carbon emissions (Eia 2018). Technological advancements and energy efficiency improvements have in plow driven the reduction in energy intensity (Metcalf 2008; Sue Wing 2008).

At the aforementioned fourth dimension that energy intensity has fallen, the carbon intensity of energy utilisation has also fallen in each of the major sectors (shown in effigy 5b). Improved methods for horizontal drilling have led to substantial increases in the supply of low-toll natural gas and less utilise of (relatively carbon-intensive) coal (CEA 2017).7 Technological advances have besides helped essentially reduce the cost of providing power from renewable energy sources like wind and solar. From 2008 to 2015, roughly two thirds of falling carbon intensity in the ability sector came from using cleaner fossil fuels and i third from an increased utilise of renewables (CEA 2017). Not-hydro-powered renewable energy has risen essentially over a curt menses of time, from 4 percent of all net electricity generation in 2009 to 10 per centum in 2018 (EIA 2019a; authors' calculations).

Fact vi: The price of renewable energy is falling.

The declining toll of producing renewable energy has played a key office in the trends described in fact 5. Figure half-dozen shows the declining prices of solar and wind energy—not including public subsidies—over the 2010–17 catamenia. Because these price decreases accept followed largely from applied science induced supply increases, solar and wind free energy now play a more-important role in the U.S. free energy mix (CEA 2017). In many settings, still, clean energy remains more expensive on average than fossil fuels (The Hamilton Projection [THP] and the Energy Policy Plant at the University of Chicago [Ballsy] 2017), highlighting the need for continued technological advances.

The increasing share of renewables in free energy supply is due in part to toll-reducing advances in engineering science and increased exploitation of economies of calibration. Government subsidies—justified past the social costs of carbon emissions—for renewable energy take besides played a role. When the negative spillovers from COii emissions are incorporated into the price of fossil fuels, many forms of clean energy are far cheaper than many fossil fuels (THP and EPIC 2017). Yet, making a much broader use of clean energy faces technological hurdles that have not however been fully addressed. Renewable free energy sources are in many cases intermittent—they make power only when the wind blows or the sun shines—and shifting towards more than renewable energy production may require substantial improvements in battery technology and changes to how the electricity market prices variability (CEA 2016). The technological developments that drive falling clean energy prices are the product of public and individual investments. In a Hamilton Project policy proposal, David Popp (2019) examines means to encourage faster development and deployment of clean energy technologies.

Fact 7: Some emissions abatement approaches are much more costly than others.

There are many ways to reduce net carbon emissions, from better livestock management to renewable fuel subsidies to reforestation. Each of these abatement strategies comes with its own costs and benefits. To facilitate comparisons, researchers have calculated the cost per ton of COii-equivalent emissions.eight We prove high and low estimates of these average costs in effigy 7, reproduced from Gillingham and Stock (2018).9

Less-expensive programs and policies include the Clean Ability Plan—a since-discontinued 2014 initiative to reduce ability sector emissions—every bit well as methyl hydride flaring regulations and reforestation. By dissimilarity, weatherization assistance and the vehicle trade-in policy Greenbacks for Clunkers are more than expensive (run into figure 7). Information technology is important to recognize that some policies may accept goals other than emissions abatement, as with Cash for Clunkers, which likewise aimed to provide fiscal stimulus later on the Cracking Recession (Li, Linn, and Spiller 2013; Mian and Sufi 2012).

Just when the goal is to reduce emissions at the lowest cost, economic theory and mutual sense suggest that the cheapest strategies for abating emissions should be implemented beginning. State and federal policy choices can play an of import part in determining which of the options shown in figure seven are implemented and in what order.

A common approach is to impose certain emissions standards—for example, a low-carbon fuel standard. The difficulty with this arroyo is that, in some cases, standards crave abatement methods involving relatively high costs per ton while some low-cost methods are non implemented. This tin can reflect government regulators' limited information most abatement costs or political pressures that favor some standards over others. By contrast, a carbon price—discussed in facts 8 through 10—helps to achieve a given emissions reduction target at the minimum toll by encouraging abatement actions that cost less than the carbon price and discouraging actions that toll more than that price.

However, policies other than a carbon price are often worthy of consideration. In a Hamilton Project proposal, Carolyn Fischer describes the situations in which clean performance standards can exist implemented in a relatively efficient manner (2019).ten

Fact 8: Numerous carbon pricing initiatives take been introduced worldwide, and the prices vary significantly.

At the local, national, and international levels, 57 carbon pricing programs have been implemented or are scheduled for implementation across the world (World Bank 2019). Effigy 8 plots some of the primal national and U.Southward. subnational initiatives,

showing carbon taxes in green and cap and trade in purple. Past imposing a cost on emissions, a carbon price encourages activities that tin can reduce emissions at a cost less than the carbon price.

Immediately apparent from figure 8 is the wide range of the carbon prices, reflecting the range of carbon taxes and aggregate emissions caps that different governments have introduced. At the highest end is Sweden with its price of $126 per ton; by contrast, Poland and Ukraine have imposed prices only above nix.11 A sufficiently high carbon cost would modify the cost-benefit assessment of some existing nonprice policies, every bit described in a Hamilton Project proposal by Roberton Williams (2019).

A crucial question for policy is the appropriate level of a carbon price. According to economic theory, efficiency is maximized when the carbon price is equal to the social cost of carbon.12 In other words, a carbon price at that level would not simply facilitate the adoption of the lowest-toll abatement activities (equally discussed nether fact 7) but would besides achieve the level of overall emissions abatement that maximizes the difference between the climate-related benefits and the economical costs.13 Although setting the carbon price equal to the social cost of carbon maximizes net benefits, the monetized environmental benefits also exceed the economic costs when the carbon toll is below (or somewhat above) the optimal value.

Estimates of the social cost of carbon depend on a wide range of factors, including the projected biophysical impacts associated with an incremental ton of COii emissions, the monetized value of these impacts, and the discount rate applied to convert futurity monetized damages into current dollars.xiv As of 2016, the Interagency Working Group on Social Price of Carbon—a partnership of U.Due south. authorities agencies—reported a focal gauge of the social price of carbon (SCC) at $51 (adapted for inflation to 2018 dollars) per ton of CO2 (indicated by the dashed line in figure viii).15

Fact nine: Most global GHG emissions are still not covered by a carbon pricing initiative.

Just as of import as the carbon price is the share of global emissions facing the toll. Many countries do not price carbon, and in many of the countries that do, of import sources of emissions are not covered. When implementing carbon prices, policymakers accept tended to offset with the ability sector and exclude some other emissions sources like energy-intensive manufacturing (Fischer 2019).

The carbon pricing systems that exercise exist are not evenly distributed across the earth (World Bank 2019). Programs are heavily concentrated in Europe, Asia, and, to a lesser extent, North America. This distribution aligns roughly with the distribution of emissions, though the Us is an outlier: every bit discussed in the introduction, Europe has generated 33 percent of global COtwo emissions since 1850, the United States 25 percentage, and China xiii percent (Ritchie and Roser 2017; authors' calculations). According to currently scheduled and implemented initiatives, in 2020 the Us volition be pricing only 1.0 percent of global GHG emissions; by comparison, Europe will be pricing 5.5 percent, and China will be pricing 7.0 percent (run into figure 9).

Figure 9 shows each region's priced emissions—including both implemented and planned (in 2020) carbon pricing—as a share of full global emissions. Between 2005 and 2012, the European Marriage's cap and trade programme was the only major carbon pricing programme. Nonetheless since the Paris Agreement, at that place has been a growing number of implemented and scheduled programs, with the largest of these existence China's national cap and trade plan prepare to have effect in 2020. Despite this activity, it is likely that a carbon price will still not exist practical to 80 percent of global emissions of GHGs in 2020 (World Banking concern 2019; authors' calculations).

Fact 10: Proposed U.South. carbon taxes would yield significant reductions in COtwo and environmental benefits in excess of the costs.

To assess proposals for a national U.S. carbon toll, it is important to understand the size of the probable emissions reduction. Figure x shows projections of emissions reductions from Barron et al. (2018) under different assumptions about the level and subsequent growth charge per unit of a U.Southward. carbon toll. Over the 2020-thirty period a carbon tax starting at $25 per ton in 2020 and increasing at i pct annually above the rate of inflation achieves a reduction in CO2 of 10.5 gigatons, or an 18 pct reduction from the baseline (emissions level in 2005). A more than-ambitious $fifty per ton price, rise at 5 per centum subsequently, would reduce virtually-term emissions past an estimated 30 percentage.16

A major attraction of using carbon pricing to accomplish emissions reductions (equally compared to adopting standards and other conventional regulations for this purpose) is its power to induce the market to adopt the everyman-cost methods for reducing emissions. As of tardily 2019, nine U.Southward. states participate in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), in which electric power plants merchandise permits that currently have a market price of effectually $5.20 per short ton of carbon 10. Proposed U.Due south. carbon taxes would yield meaning reductions in CO2 and environmental benefits in excess of the costs. (RGGI Inc. 2019).17 That means that electric power plants covered under the RGGI are able to find methods of emissions abatement at a cost of $5.20 per ton at the margin and would buy permits at that cost rather than undertake whatever abatement opportunities at a college cost. A lower aggregate cap—or a college carbon tax—would continue to select for the abatement approaches that have the lowest costs per ton for a given sector.

Even at much higher levels, emissions pricing leads to environmental benefits—reduced climate and other environmental amercement—that exceed the economic sacrifices involved (i.east., the expense of reducing emissions).xviii A cardinal approximate of the social toll of carbon (in 2018 dollars) is $51 per ton (Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Carbon 2016). However, many recent proposals have tended to entail carbon prices below this level.nineteen Goulder and Hafstead (2017) discover that a U.Southward. carbon tax of $20 per ton in 2019, increasing at 4 percent in existent terms for 20 years after that, yields climate related benefits that exceed the economic costs by about 70 percent.twenty

The authors did not receive financial back up from whatsoever house or person for this article or from any house or person with a financial or political interest in this article. None of the authors is currently an officer, managing director, or lath member of whatsoever organization with a financial or political involvement in this article.

How Does Climate Change Affect The Economy,

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/research/ten-facts-about-the-economics-of-climate-change-and-climate-policy/

Posted by: robbinssencong.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Does Climate Change Affect The Economy"

Post a Comment